According to Nietzsche, there are no facts, only interpretations. However you may feel about that in general, I hope to convince you that gender (in a wide sense, to include sex) is best understood as an interpretation, not a fact. For example, I behold you, and assign “female”, or “male”, or perhaps some other gender to you, or not, based on what I think of you and know about you, and based on my own perspective on gender.

But different people have different perspectives on gender, and so assign gender differently to the same people. That is, we make different interpretations of the same beings. And what’s more, we use different perspectives in different contexts, for example, social versus sexual, or private versus public.

Most importantly, there is no “one true” perspective on gender, that is, gender is subjective and not objective. Here I am going to discuss a variety of perspectives on gender, and how these perspectives each emphasise and deemphasise particular elements, particular aspects of nature and culture that are frequently considered gendered.

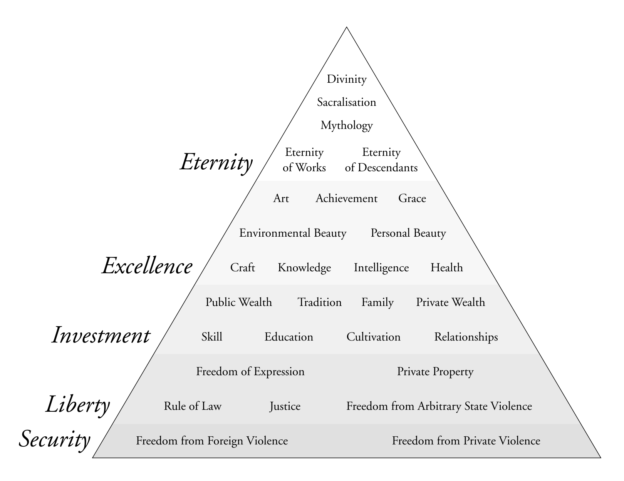

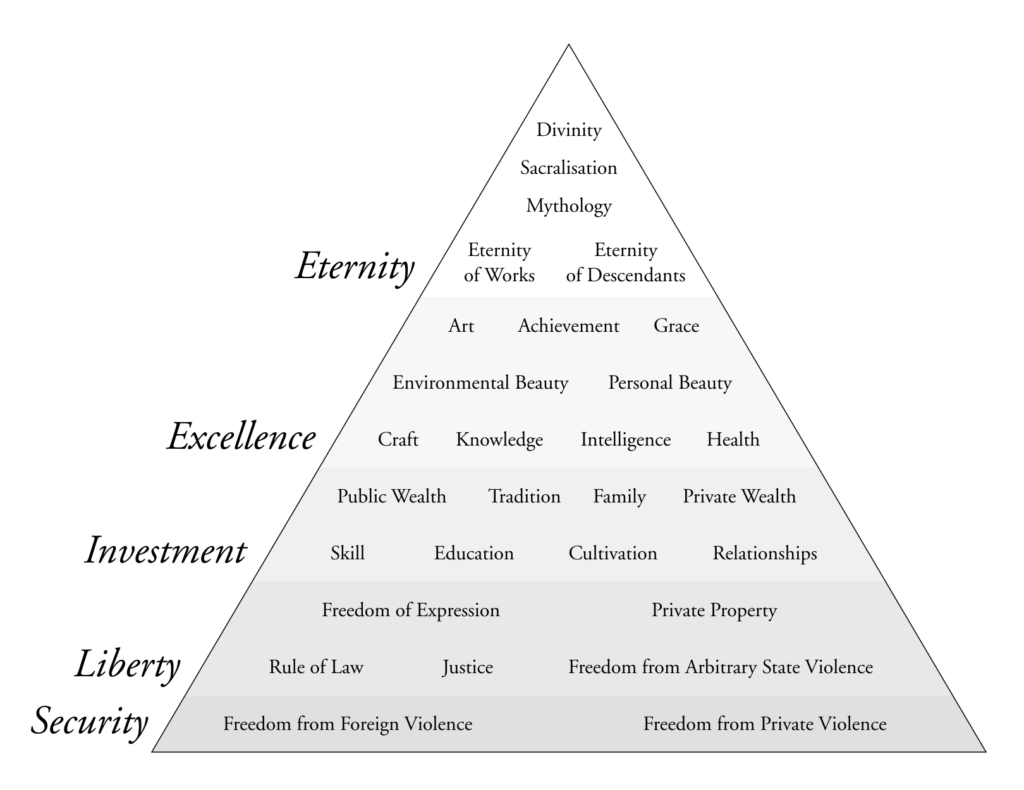

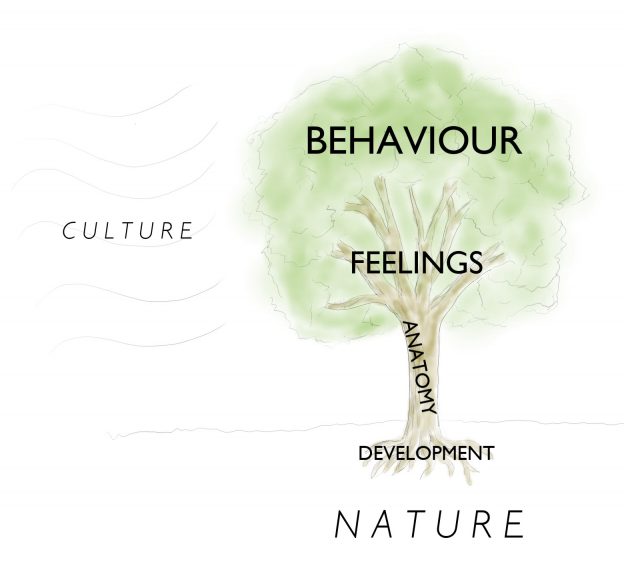

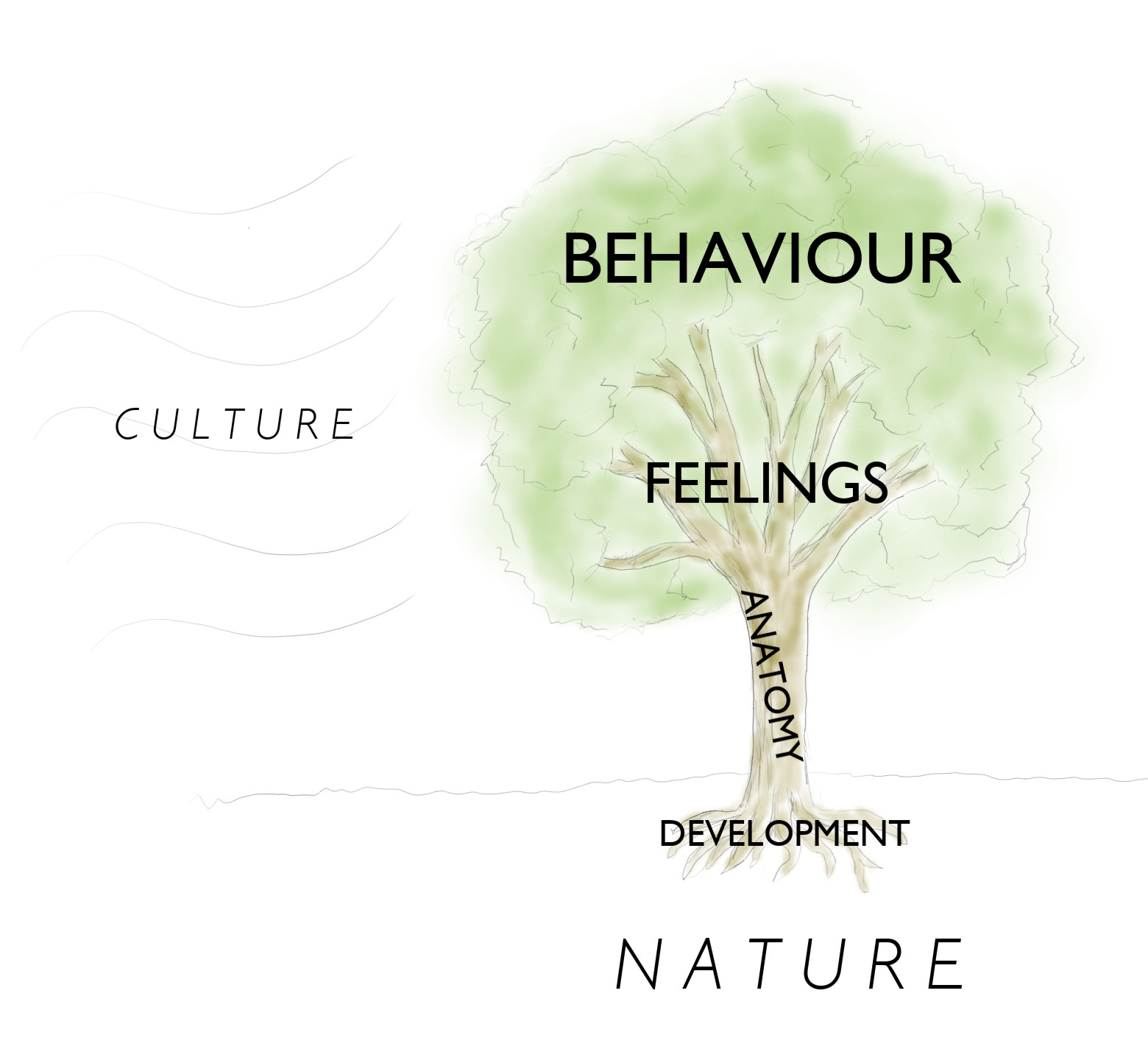

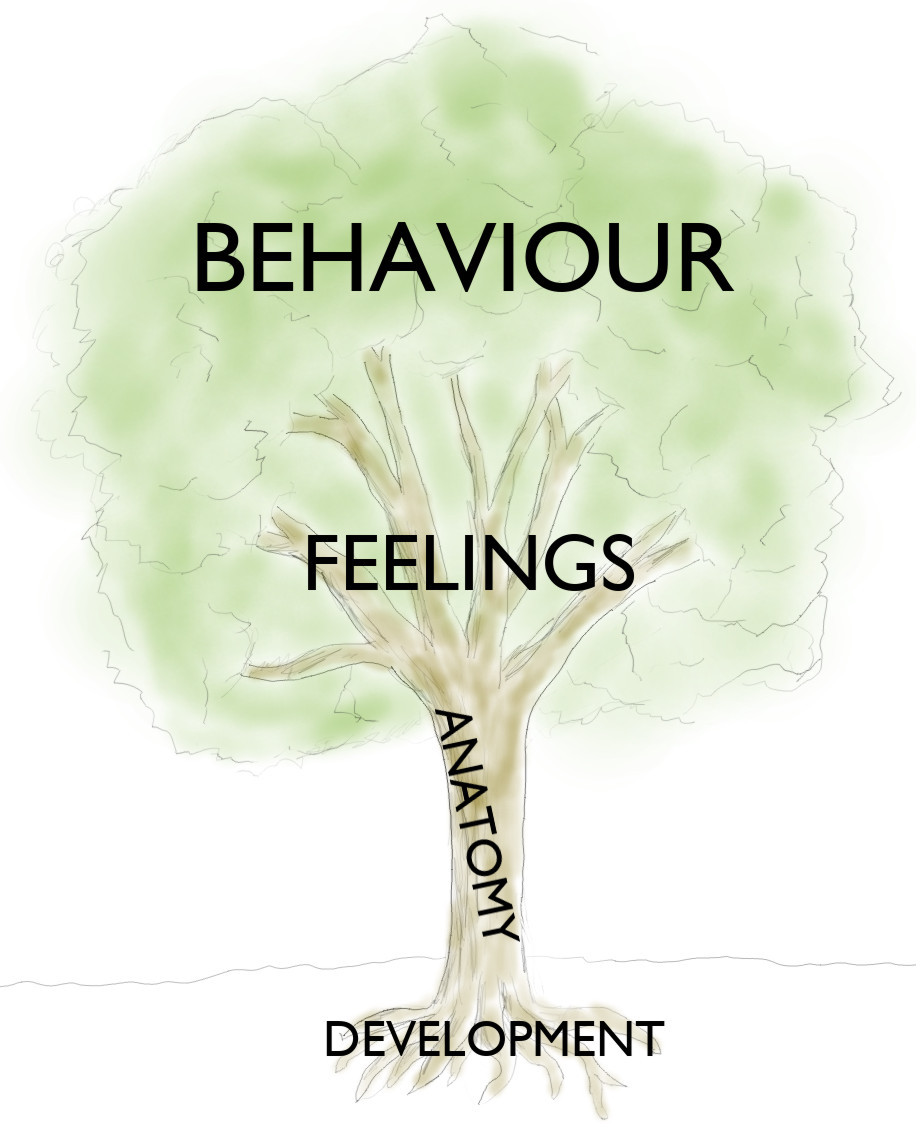

I want you to imagine a tree. The earth the tree grows in is nature, the cycle of fertility, sex, and childbirth, created and recreated by the evolutionary forces of mutation and selection, the purpose of gender and the reason why it exists at all. This reproductive purpose is the source of the inevitable binarity that pervades notions of gender generally, and perhaps inevitably justifies a certain amount of cis-hetero-centrism.

The roots of the tree are biological and developmental factors such as allosomes, TDF protein presence/absence, sex steroids (i.e. androgens, œstrogens).

The trunk is bodily anatomy, not only sex organs but all sexual dimorphism, including differences in brain biology. Some of this is surgically malleable, much more of it is not.

The branches are gender identity, thoughts, feelings, reactions, our sense of self.

The leaves, growing from and somewhat obscuring the branches, are gender roles, speech, behaviour, how we express ourselves, the clothes we wear, the choices we make, all things masculine and feminine.

The winds of culture blow the branches and especially the leaves.

Which of these things truly determines a person’s gender?

Leaves First

We acquire our first notions of gender at around age two or three. These tend to be based more on dress and social expectations than on genital anatomy, and may not even consider gender to be a constant fact about oneself or others. Tests on children showing pictures of babies naked and with gender-appropriate or -inappropriate clothes, show that many three-year-olds determine gender solely by social cues. This changes, of course, as we grow older.

It’s easy to think that these three-year-olds are mistaken about gender, lacking “genital knowledge”, the way kids are mistaken about lots of things. But we’ve given up objectivity: no views of gender are “correct” or “incorrect” in any absolute sense. Children merely make various gender interpretations as they learn about it. But these interpretations, though they are not facts, are still subject to criticism, based on how useful or appropriate they are in a given context. One can call children’s inconstant interpretations of gender useless or inappropriate, ones that will be replaced by better interpretations, but one cannot call them inaccurate as such — except with reference to some other theory of gender.

The Snag Radical Feminist Tree

The radical feminist view of sex and gender is today deeply unfashionable. As a result, those putting forth this view have had to be much more careful and much more charitable in presenting their arguments to be taken at all seriously.

While I have been using gender in a broad sense, the radical feminist view typically distinguishes “sex” from “gender” in a narrower sense. Roughly, the roots and the trunk of the tree are “sex”, while the branches and leaves are “gender”. Sex is natural and biological, while gender is behaviour that is a product of culture, specifically an all-pervading theme of culture they call “patriarchy”. Femaleness and maleness, as well as womanhood and manhood, apply to biological sex, and not social gender. Gender is, in this view, a wholly negative phenomenon, not part of one’s true self or true consciousness, especially not for women, and for this reason, the view is also called gender-critical.

This article gives a pretty good view of the radical feminist or gender-critical concept of biological sex:

Several of us endorse a cluster account of femaleness, according to which possession of some vague number of a certain set of endogenously-produced primary sex characteristics — including vagina, ovaries, womb, fallopian tubes, and XX chromosomes — is sufficient for femaleness, though no particular characteristic is necessary or essential.

This is what makes someone female, or male. The roots and trunk of the tree are what matters. To sever the branches from the trunk, this view typically considers that “mind has no sex”, and gendered behaviour is entirely artificial and cultural. The gender-critical project is actually to abolish social gender entirely.

In the radical feminist view, why does transgender arise? Why do men, as they say, claim to be women, and why do women claim to be men? It is an axiom of radical feminism that society privileges men entirely above women. So for the latter case, trans men are simply women who desire the privileges of being accepted as men. The former case might pose more of a puzzle, but it is generally chalked up to a kind of bottomless well of male sexual perversity, or even the specific desire to invade women-only spaces. This fits in with an overall negative view of men in general.

The radical feminist view of gender is consistent, but depends on a “blank slate” view of gender. A thought-experiment to illustrate this: let us say you had a newborn girl and a newborn boy, and magically surgically swapped their brains. Would they be more likely than otherwise to (1) grow up homosexual (relative to their genitalia)? (2) experience gender dysphoria, the persistent feeling of being in the wrong-gendered body? (3) end up preferring to inhabit the opposite (relative to their genitalia) social gender roles? I think the radical feminist answer is “no” to all three, though this leaves no answer to the question, why are some people homosexual and others heterosexual?

Identity

What is identity? There are two sides to it. Internal identity is how you think of yourself, while external identity is how others think of you, how they identify you and differentiate you from others. It’s easy to think of internal identity as prior “true” identity, and external identity as following on from that, as merely other’s knowledge of your internal identity, which may be accurate or inaccurate. But actually I think external identity comes first, and internal identity is what you want others to think about you, your desires for external identity. You can think of external identity as “identity achieved” and internal identity as “identity desired”.

Both kinds of identity are important. To disregard external identity is narcissistic, insisting that others think about you only in the way you wish. To disregard internal identity is authoritarian, forcing you to conform to the needs of others. And it is normal, not unusual, for the two kinds of identity to be in tension, this kind of struggle to achieve a desired identity is part of what it means to be human. If gender is “performative” in any sense, it is this struggle, the actions we do to encourage others to think of us in particular ways.

Natalie Reed’s definition of gender identity is an example of what I mean by internal identity:

Gender Identity – The inner conceptual sense of self as “man”, “woman” or other, as divorced from issues like gender expression, sexual orientation, or physiological sex. It is a subtle and abstract, but extremely powerful, sense of who you are, in terms of gender, independent of how you dress, behave, what your interests are, who you’re attracted to, etc.

Some people claim not to experience any such internal sense of gender. But if internal identity is understood as a desire for external identity, that’s unsurprising. We don’t typically experience desire for things we already have: at the very least, we must first reflect on the possibility or threat of their absence. So if you’re already socially recognised as the gender you want, you are unlikely to give the matter any thought. If you’re unsure whether you have internal gender identity, ask yourself, if your brain were transplanted into the body of the other sex, and were socially recognised as that sex, would your new external gender identity trouble you?

It’s worth mentioning that internal gender identity is not even necessary for a useful concept of gender. From an external perspective, newborn babies have gender, most animals have gender, even some plants have gender, without (apparently) having any internal gender identity or engaging in performative acts.

The Deracinated Trans-Activist Tree

In its simplest form, the trans-activist view defines gender entirely by internal identity, that is, you are female if you consider yourself to be female. Biological structures such as womb, penis, are not themselves gendered and their presence or absence have no bearing on gender. This view of gender is a deracinated tree, with little trunk and no roots connecting it to its origin and reproductive purpose.

In extreme form, this view wishes to entirely erase any connection between anatomy and gender in any context. So for example, a woman who identifies as lesbian is “transphobic” if she is not attracted to trans women, because lesbian can only mean a woman who is attracted to women irrespective of anatomy and genitalia, and trans women are plainly women.

Furthermore, if genitalia are not gendered, then a preference for one kind of genitalia over the other kind has nothing to do with gender either. So, logically, “gender dysphoria” has nothing to do with gender either: it’s merely a desire or need for one (ungendered) kind of genitalia over the other (ungendered) kind of genitalia. For example, a woman has a penis, but in this view it’s a female penis, because it belongs to a woman. Then the desire to replace this female penis with a female vagina has nothing to do with gender, because the genitalia are female either way. This seems to erase a common theme of transgender experience.

As such, the self-identity definition is circular. It raises the question, when you identify as female, what do you mean by female?

Transmedicalism Redeeming the Trunk

One way of avoiding this circularity is to root gender in brain biology. This view rejects the claim that mind has no sex, and accepts a sexed difference in brain development. This leads to the possibility of dysphoria, when due to occasional developmental circumstances, the brain is sexed differently from the rest of the body. Defining transgender in terms of dysphoria is known as transmedicalism.

This also admits the possibility that gendered behaviour, masculinity and femininity, are rooted in brain biology, albeit expressed in culturally-determined forms. People may tend to be, on average, biologically predisposed to inhabit gender roles. This would explain the widespread cross-cultural persistence of certain themes of masculinity and femininity.

There is a parallel, indeed, between gender identity and gender preference: some part of the brain says to the self “I desire women rather than men”, while another part of the brain says to the self “I am a woman rather than a man”.

Looking at the trunk of our tree, there are a large cluster of anatomical differences between men and women, with which we might construct a notion of “anatomical” or “biological” maleness and femaleness. Medical and surgical interventions alter some of this gendered biology, especially those affecting the social perception of gender, while much else is left unaltered. Thus, in the transmedicalist model, the body starts from one’s natal gender, but through hormones and surgery, becomes partly but not completely the other gender, redeeming the dissonance between brain and anatomy.

Transmedicalism’s focus on the signficance of transgender dysphoria (somatic or social) comes from a consistent and credible model of gender, however, its insistence on dysphoria as a necessary defining characteristic of the word “transgender” may exclude other useful interpretations of gender. The theory of mismatch between brain development and anatomy is a reasonable foundation for the concept of transgender, but it may not be the only foundation.

Public Policy

Who should be permitted in womens’ and mens’ restrooms? Who should be incarcerated in women’s and men’s facilities? Who should be permitted in women’s sports? How do we resolve gendered questions of public policy?

Rather than attempting to establish a single objective definition of gender for all public policy purposes, I believe it is necessary in each case to first establish the purpose of gender distinction, and then come up with a specific definition of gender, or more generally a policy, that best serves that particular purpose. This inevitably means that some people will be, for example, “female” in general social contexts, and “male” when competing in sports.

Sports provide an interesting case. Sporting events desire the very best athletes; when considering the population as a whole, these will almost always be young adult men. A gender-neutral policy will thus have a highly gendered outcome, just as it has a highly age-specific outcome. To ameliorate this, or at least to provide more variety of sports spectacle, it is common in many sports to create an additional league restricted to women. One could likewise create special restricted leagues for those over the age of forty, or those under a particular height, or those of a particular weight as is actually done in boxing.

For qualification to women’s sports leagues, the appropriate approach is to consider those aspects of gender that affect athletic performance, such as testosterone level both present and at puberty. However at present there seems to be no obvious single standard, leaving instead a contentious trade-off of concerns. The International Olympic Committee, for example, has set a guideline of a particular serum testosterone level, but is now considering restricting it.

If someone qualifies to compete in a women’s sports league, because of some quality of their blood, does that make them a woman? Is it, at least, an act of recognition of womanhood? Actually it is merely one more interpretation of gender for one particular purpose, relevant in that context and not in others.

Contextual Views

People already use different conceptions of gender in different contexts, perhaps using the self-identity standard (the branches of the tree) in ordinary social situations, and anatomy and signals of fertility (the trunk of the tree) when examining their own sexual desires. The former is not necessarily mere “courtesy of pronouns” but can be a genuine perception of someone as the gender they say they are, in that social context.

For sexual desire, however, the self-identification conception of gender cannot be the definitive last word in determining the genderedness of attraction. Some people are bi- or pan-sexual, but many (probably most) have a preference for one sex over the other. These preferences tend to be more or less involuntary and immutable (witnessing the failure of “conversion therapy”) and strongly influenced by anatomy, including genitalia. This should not be surprising, given that gender and its tendency towards binarity ultimately originate in fertility and reproduction.

A contextual approach to gender interpretation frees social recognition of gender from sexual desire. It permits situation-specific approaches to gender in public policy without making or relying on objective declarations of gender. It frees others to interpret you as they will, while accepting the legitimacy of your choices of self-presentation on which others’ interpretations are based.

— Ashley Yakeley